Only members can weigh in.

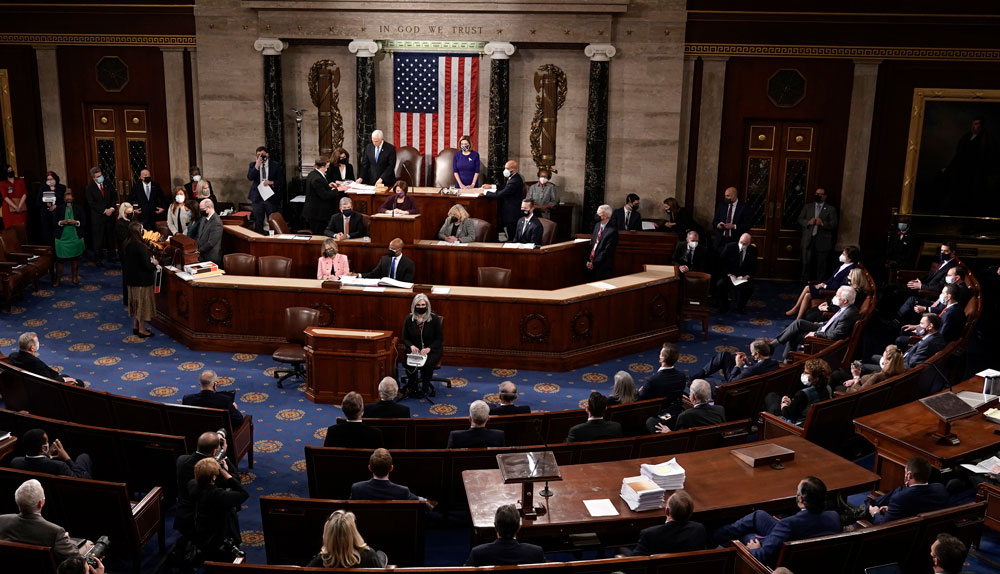

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and Vice President Mike Pence officiate as a joint session of the House and Senate convenes to confirm the Electoral College votes cast in November's election, at the Capitol in Washington, Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2021. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

For very different reasons, leaders of both parties have been questioning whether we can trust the results from our elections. A lack of faith in our election outcomes on both the left and right poses a serious threat to American self-government. The ability to trust that our representatives have been determined by the voice of the people is the bedrock of the most successful republic in history.

Both the left and right have pursued elections measures that are unrealistic this year because the other side vigorously opposes them. Efforts to find measures wise enough to attract support across the partisan divide are, however, making impressive progress. Those efforts include the work by a bipartisan group of roughly 16 senators led by Senators Manchin (Democrat – West Virginia) and Collins (Republican – Maine). This is largely the same group with whom we successfully worked on infrastructure legislation last year.

Several of the most influential senators in this group encouraged us to pick this issue because they believe we could play a significant role by demonstrating whether, and where, broad consensus exists among the American people. Even more than on our previous issues, Congress is eager to hear what CommonSense Americans think about elections legislation.

This brief provides you with information to form your own judgment about the wisdom of legislative proposals under active consideration in four areas:

- Electoral Count Act (ECA)—Passed by Congress in 1878, the ECA establishes how and when states certify and send the results of the presidential election to Congress. It also establishes how Congress counts the electoral votes and resolves disputes.

- Presidential Transition Act (PTA)—The PTA governs how and when a president-elect receives a range of resources so that they can prepare to lead effectively as soon as they are sworn in.

- State and Local Funding—Congress is considering proposals to increase federal funding for state and local governments to administer elections.

- Election Worker Protection—Several measures have been proposed to protect election workers against growing threats.

Elections Experts

CommonSense American is grateful to the more than 30 top elections experts and leaders in the nation who helped us develop this brief. They come from across the political spectrum and provided invaluable assistance in our effort to represent the proposals accurately and the competing perspectives fairly.

We also express our thanks to the 11 of our 30 advisors who joined us when we announced our results on June 27.

CommonSense American is the final author of this brief. Any inadequacies are ours.

Trey Grayson

Former Republican Secretary of State in Kentucky, President of the National Association of Secretaries of State, Chair of the Republican Secretaries of State Association. Director of Harvard University’s Institute of Politics. Special thanks to Trey, also a founding NICD board member, for his considerable work helping us integrate the insights from all the other experts into a single, coherent brief.

Bob Bauer

White House Counsel to President Obama, former Co-Chair Presidential Commission on Election Administration, Professor of Practice and Distinguished Scholar in Residence at NYU School of Law.

Ben Ginsberg

Counsel to Bush-Cheney and Romney-Ryan campaigns; former Counsel to the Republican National Committee, National Republican Senatorial Committee, and National Republican Congressional Committee; and former Co-Chair of Presidential Commission on Election Administration.

Edward B. Foley

Charles W. Ebersold and Florence Whitcomb Ebersold Chair in Constitutional Law; Director, Election Law, Ohio State University

Rick Pildes

Sudler Family Professor of Constitutional Law, NYU School of Law

Courtney Simmons Elwood

Former CIA General Counsel in Trump Administration and former Associate White House Counsel in George W. Bush Administration

Steve Bradbury

Former General Counsel, Department of Transportation in Trump Administration and former Head of Office of Legal Counsel, Department of Justice in George W. Bush Administration

Judge Michael McConnell

Richard and Frances Mallery Professor and Director of the Constitutional Law Center at Stanford Law School, Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, former Judge on the United States Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals

Jack Goldsmith

Learned Hand Professor of Law, Harvard Law School; former Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel in George W. Bush Administration

Judge J. Michael Luttig

Former Judge on the United States Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals; former Associate White House Counsel, Reagan Administration

Matthew Seligman

Fellow, Center for Private Law, Yale Law School.

Rick Hasen

Professor and Director, Safeguarding Democracy Project, UCLA School of Law; founding co-editor of Election Law Journal

David Stafford

Supervisor of Elections, Escambia County, Florida

Michael Herz

Arthur Kaplan Professor, Cardozo Law School; former Chair of ABA’s Section of Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice

Kate Shaw

Professor and Co-Director of the Floersheimer Center for Constitutional Democracy, Cardozo Law School.

Norm Ornstein

Senior Fellow Emeritus, American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and former Codirector, AEI-Brookings Election Reform Project.

David Becker

Executive Director and Founder of Center for Election Innovation & Research and former Director of the elections program and The Pew Charitable Trusts

Charles Stewart Ⅲ

Kenan Sahin Distinguished Professor of Political Science, MIT; Founding Director, MIT Election Data & Science Lab; author of The Cost of Conducting Elections co-produced with NICD’s CommonSense American program

Jocelyn Benson

Secretary of State, Michigan

Shenna Bellows

Secretary of State, Maine

Leigh M. Chapman

Acting Secretary of the Commonwealth, Pennsylvania

Maggie Toulouse Oliver

Secretary of State, New Mexico

Steve Simon

Secretary of State, Minnesota

Wayne Williams

Former Secretary of State, Colorado

Bill Gates

Chair, Maricopa County (Arizona) Board of Supervisors

Matt Masterson

Former U.S. Election Assistance Commissioner and Former Interim Chief of Staff and Deputy of Elections for the Ohio Secretary of State

David Stafford

Supervisor of Elections, Escambia County, Florida

Chris Piper

Former Commissioner, Virginia Department of Elections

Karen Brinson Bell

Executive Director, State Board of Elections, North Carolina

Joseph Kirk

Election Supervisor, Bartow County, Georgia

Rebecca Green

Associate Professor of Law and Co-Director, Election Law Program, William & Mary Law School

Tiana Epps-Johnson

Executive Director, Center for Tech and Civic Life

Lori Augino

Executive Director, National Vote at Home Institute

Tammy Patrick

Senior Advisor, Elections, Democracy Fund

Electoral Count Act

Vice President Mike Pence and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., read the final certification of Electoral College votes during a joint session of Congress at the Capitol in Washington, Thursday, Jan. 7, 2021. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, Pool)

For over a century, the procedures that Congress followed to count the votes in the Electoral College on January 6 following a presidential election amounted to a mere formality. After all, any questions about the vote had been resolved weeks in advance. In the past two decades, however, that has changed. The congressional certification of the electors of each state is no longer simply a ceremonial formality.

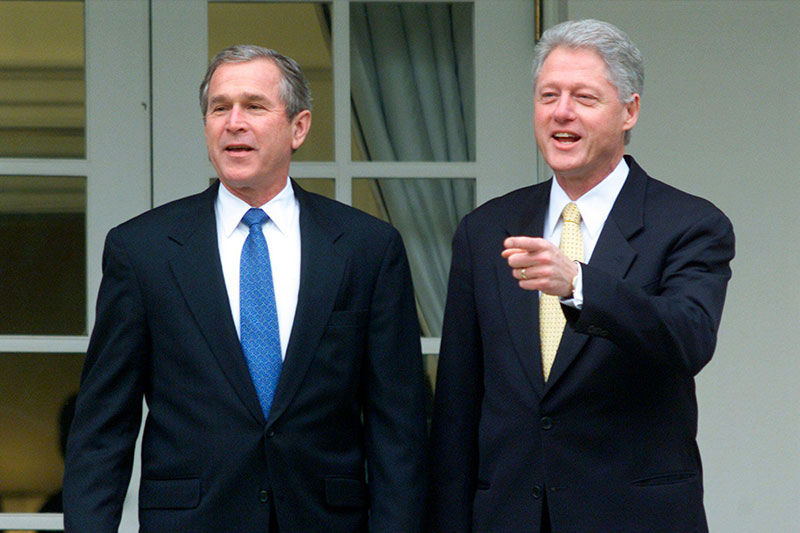

It started with congressional Democrats. Beginning with the 2000 presidential election, Democrats have objected to the last three Republican presidential wins. About a dozen House Democrats objected to Florida’s electoral votes during the 2000 certification, but their efforts failed for lack of any Senate support. Four years later, after the 2004 presidential election, a group of 31 House Democrats, joined by a single Senate Democrat, objected to Ohio’s electoral votes, triggering a two-hour debate before Ohio’s slate of electors was accepted. Twelve years later, after Donald Trump’s 2016 win, a half dozen House Democrats objected to the certification of the electors of several states that Trump won but they found no senator willing to join them.

An even more serious departure from the century long practice of bipartisan respect for the established presidential election process followed the 2020 presidential election. President Trump and some Republican allies attempted to circumvent that process and reverse the result of the election in several ways.

First, President Trump and his allies attempted to convince state legislatures in states where President Biden had been certified as the winner to submit slates of electors favoring President Trump instead. They also pressured governors and other state officials in several states to certify Trump’s electors rather than the Biden electors that had legitimately won the state’s election. In addition, they attempted to convince Vice President Mike Pence to assert unilateral authority to reject certain states’ electoral votes.

Finally, President Trump and his allies organized a campaign for members of Congress to raise objections to counting certain states’ electoral votes on January 6, invoking unsubstantiated allegations of voter fraud and other improprieties that had already been rejected by the courts. As a result, six Republican senators and 121 Republican members of the House voted to object to Arizona’s electoral votes, while seven Republican senators and 138 Republican members of the House voted to object to Pennsylvania’s electoral votes. Plans to object to the electoral votes of as many as five other states were abandoned after the violent attack on the Capitol Building interrupted the Joint Session of Congress.

The escalating attempts by both parties to challenge the results of presidential elections have convinced many Republican and Democratic members of Congress, scholars, and election experts that the law governing the counting of electoral votes must be updated. There is wide bipartisan agreement that this law – the Electoral Count Act of 1887 (ECA) – is vague, antiquated, and nearly impossible to interpret.

Many members of Congress and others are particularly concerned that the existing ECA is vulnerable to politically motivated manipulation by Congress or by state officials. After all, we have seen members of Congress from both parties object to state electors during several recent elections. It isn’t a stretch to see how members, feeling pressure from their party might manipulate the results in a future election by voting to reject legitimate electoral votes.

As most Americans know, U.S. Constitution establishes a unique system for electing the president that is different in important respects from the elections we hold for any other public office. Instead of voting directly for the presidential candidates, Americans technically vote for electors selected by the candidates and their political parties. Those electors then cast votes for the presidential candidates in the Electoral College.

READ MORE

The Constitution, as amended by the Twelfth Amendment, established an Electoral College that creates a two-stage process. In the first stage, the states appoint electors. Each state is allotted a number of electoral votes equal to the state’s total number of members of Congress in the Senate and the House of Representatives. (The Twenty-Third Amendment gives the District of Columbia three electoral votes, even though it is not represented in Congress.) States have flexibility in deciding how to appoint their electors – though since the middle of the 19th century every state has done so through a popular election.

In the second stage, once the states have appointed their electors, the electors cast their ballots in the Electoral College. In modern times, electors pledge in advance to vote for one of the candidates and many states have laws requiring electors to comply with their pledge. In practice, this means that each state’s electoral votes are cast for the candidate who wins the popular election in the state. (Maine and Nebraska have a slightly different system – some of their electoral votes are awarded to the winner of the statewide election, and some are awarded to the candidate who won the most votes in each congressional district.)

This two-stage process under the Constitution provides roles for both states and Congress. The Electors Clause of Article II of the Constitution preserves considerable discretion for states in how to choose electors: “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, [its] Electors.” But the Constitution also gives Congress the power to determine when electors must be chosen: “The Congress may determine the Time of chusing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.” Congress has exercised that timing power in the 3 U.S.C. §§ 1-2. Section 1 requires that states appoint electors on Election Day. Section 2 creates a limited exception to that requirement: if a state holding a popular election “failed to make a choice” on Election Day, then the state can appoint electors later “in such a manner as the legislature of such state may direct.” Congress enacted that exception in 1845 to allow states that require a majority winner (rather than just a plurality, meaning the most votes of any candidate but still less than 50%) to hold run-off elections, and possibly also to give states flexibility if a natural disaster prevents people from voting on Election Day. No one in Congress at the time suggested that Section 2 might apply based on claims of voter fraud or other election improprieties.

The two-stage process culminates with Congress counting the electoral votes after the electors cast them to determine which candidate has prevailed: “The President of the Senate shall, in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the Certificates, and the Votes shall then be counted.”

From early in our history, many have questioned Congress’s proper role in resolving disputes about presidential elections. That debate climaxed in the Crisis of 1876, in which officials from several states sent in competing slates of electors for different candidates. Ultimately, Congress was able to resolve that dispute, and Rutherford B. Hayes took office.

READ MORE

To “count” the 1876 electoral votes, Congress needed to determine which of these dueling submissions were valid. No one doubted that the states, and not Congress, have the constitutional responsibility for deciding how electors were to be appointed. But because it was faced with more than one piece of paper purporting to speak on behalf of the disputed states, Congress was forced to decide which submissions genuinely reflected the states’ appointment of electors. In 1876, there was no law in place governing how Congress should resolve the dispute. Because the House and the Senate were controlled by different parties, for months they couldn’t agree on how to proceed. Finally, they established an ad hoc Electoral Commission that resolved the dispute just days before Inauguration Day in 1877.

A decade after the Crisis of 1876, Congress enacted the ECA to prevent another crisis from arising in the future. The ECA establishes a process for Congress to count the electors’ votes and resolve any objections. The ECA directs Congress to treat a state’s final determination of a dispute about electors “by judicial or other methods” as “conclusive” so long as it is reached before a deadline in early December. Unfortunately, the ECA is complicated and vague and has failed to prevent members of Congress of both parties from making objections to state electoral counts that violate the ECA’s provisions. The Majority Staff of the Committee on House Administration has prepared an ECA report that provides a more complete history of the law and its applications.

READ MORE

The ECA first requires the governor of each state to send a certificate to Congress naming the state’s validly appointed electors, which in practice means that the governor sends a certificate naming the electors appointed through the state’s popular election. Then on January 6, Congress convenes to count the electoral votes. The ECA provides that for each state, the presiding officer along with several members of Congress called “tellers” open the certificates and announce the results. The vice president, who is the presiding officer, then calls for objections. If one member of the House and one senator sign the objection, the chambers separate to debate for two hours and then vote on the objection. The ECA’s procedures for resolving these objections are exceptionally complicated. In short:

- If Congress receives only one slate of electors purporting to be from a state that has been certified by the state’s governor, then Congress must count those electors’ votes unless they were not “regularly given” (the statute does not define this vague term.) To reject a single slate, both chambers of Congress must vote to reject it.

- If Congress receives multiple slates of electors purporting to be a from a state, and the two chambers agree on which one to count, then Congress counts those electors’ votes. But if the chambers disagree about which one to count, then Congress counts the slate that had been certified by the governor.

In taking these votes, the ECA directs Congress to treat a state’s final determination of a dispute about electors “by judicial or other methods” as “conclusive” so long as it is reached before a deadline in early December. However, as a practical matter there is no enforcement mechanism to ensure that Congress follows that direction. In recent years, Members of Congress have ignored the law’s requirements and made objections that were invalid because they were based on allegations that courts had already rejected.

Proposals

Over the past year and a half, members of Congress from both parties have worked to develop ECA reforms that would clarify and strengthen the process for Congress counting electoral votes. Their efforts have focused on five specific changes to the law.

1. Clarify that the Vice President has only ceremonial and procedural responsibilities

This clarification would confirm that the vice president has no substantive role in resolving disputes about electors and has no authority to reject electoral votes or to delay the proceedings.

The Case For

Supporters of this clarification argue that the Constitution vests the power to count electoral votes in Congress. Historical practice from the early years of the Republic supports that view. Congress appointed tellers to count the electoral votes beginning in 1792, and no vice president has ever attempted to exercise unilateral power to decide whether and how to count a state’s electoral votes.

Proponents contend that this constitutional history makes sense because it would be dangerous for any single person to have such expansive power to decide the results of an election. They add that the vice president is particularly likely to suffer from a conflict of interest, because he or she is frequently a candidate for re-election as vice president or for election as president. As a result, they argue, vesting the vice president with any substantive power in this proceeding creates the unacceptable risk that he or she alone would have the authority to overturn the will of the people and determine who becomes president on their own. Supporters observe that the view that the Constitution gives the vice president power to reject a state’s electors is rejected by almost all constitutional scholars. Even many supporters of President Trump agree that the Constitution does not, and should not, give the vice president the power to throw out a state’s electors on his or her own. Otherwise, in 2024 Vice President Harris would be able to dismiss the electors from states that voted for the Republican candidate.

The Case Against

Opponents of this clarification argue that the Constitution grants the vice president the authority to preside over the count, and thus to resolve disputes that arise. They further contend that no statute can limit the vice president’s powers that the Constitution grants.

2. Clarify that after Election Day a state legislature may only provide a new means to choose electors if there has been a major natural disaster or a similarly catastrophic event

The ECA currently establishes a timeline by which states must complete different steps in the process of determining their slate of electors and sending them to Congress. In the case that a state has “failed to make a choice” by Election Day, the law gives state legislatures the ability to establish a means of designating those electors after Election Day. The history shows that Congress intended the provision to apply only in the case that a major natural disaster or similarly rare and catastrophic event disrupted Election Day. This proposal would make that meaning clearer and more explicit.

The Case For

Supporters argue that this clarification is necessary to prevent a state legislature from overturning the people’s decision in an election simply because the legislature did not like the results. A broad interpretation of the existing language in the ECA might be read to give the legislature an excuse to overturn the results based, for example, on unsubstantiated allegations of voter fraud, voter suppression, or manipulation of voting machines.

Proponents argue that the clarification would still permit states flexibility if a genuinely catastrophic event kept people from voting while also preventing politically motivated manipulation.

The Case Against

Opponents argue that this proposal unwisely limits states’ flexibility in dealing with the countless ways that the integrity of the elections can be compromised and corrupted. They contend that any list of events that Congress could draft now would inevitably fail to include problems that might arise in the decades to come.

Opponents further argue that the people’s representatives rather than courts are the best institution to respond to widespread lack of confidence in the reliability of election results, regardless of the cause of those doubts.

3. Raise the threshold for objections

Under current law, if one senator and one member of the House sign an objection, then the chambers must separate for two hours of debate and then vote on the objection. With the proposed change, debate would be triggered only if a significantly higher number of members join the objection.

The Case For

Proponents of raising the objection threshold argue that current law allows fringe objections supported by very few members of Congress. These fringe objections, they contend, have no possibility of being sustained by a majority of Congress. By setting the threshold so low, current law incentivizes political grandstanding instead of serious debate.

A higher threshold still ensures that the minority party gets heard. In the past century, supporters observe, no party has ever controlled three-quarters of both chambers.

Supporters also argue that the current low threshold risks giving the false impression that the outcome of a clearly settled election is in genuine doubt and might be reversed. That false impression contributed to the atmosphere on January 6, 2021, they argue, that ultimately turned violent.

The Case Against

Opponents of raising the objection threshold argue that doing so would stifle debate and the airing of concerns about the election. They observe that the objection process simply triggers two hours of debate. After that debate, a majority of Congress must vote to sustain the objection for a state’s electoral votes to be rejected. Raising the objection threshold would not alter the rules for how Congress counts electoral votes, they argue, it only prevents minority views from being discussed.

4. Clarify the limited grounds for objections

There is wide concern that the ECA in its current form is unclear on what limits if any, restrict Congress’s power to reject electoral votes. That concern has resulted in a recommendation to include in the ECA a list of the specific grounds for objection that may be raised against counting a state’s electoral votes.

Two types of limited grounds for objection have been proposed. First, a member of Congress may object that the purported electors were not actually appointed by the state. For example, if the certificate is a forgery or the governor submits a certificate that does not reflect the results of the legal process in the state. Second, a member may object that an electoral vote violates the Constitution. For example, if the electoral vote was cast for a candidate younger than 35 years old. Any objections brought on other grounds, including that there was fraud or improprieties in the underlying popular election in the state, would be ruled out of order and would not be considered.

The Case For

Those who support clarifying the grounds for objections argue that the lack of clarity led to objections brought by Democrats in 2001, 2005 and 2017 and Republicans in 2021 that exceeded Congress’s proper role under the Constitution because states appoint electors, not Congress.

Supporters also assert that the Constitution establishes only a very limited role for Congress when it convenes to count the votes in the Electoral College. In counting the electoral votes, Congress’s authority is limited to confirming that the electors were genuinely appointed by the state and that the electoral votes are consistent with constitutional requirements. Proponents maintain that objections that scrutinize how states conducted their elections exceed those strict limits.

As Republican Leader Senator Mitch McConnell explained on January 6, 2021, “[t]he Constitution gives Congress a limited role. We cannot simply declare ourselves a national Board of Elections on steroids.” Supporters argue that those constitutional limitations are sensible. They claim that Congress is ill-equipped to investigate allegations of election improprieties, they argue. States and courts, by contrast, have extensive experience conducting recounts, considering challenges to ballots, and resolving other disputes about popular elections.

The Case Against

Opponents argue that limiting the grounds for objection would tie Congress’s hands, no matter how extensively a state’s election is plagued by fraud and illegality. In this view, Congress can serve as a final check if other institutions have failed to address grave problems in the election.

5. Clarify that Congress must honor courts’ rulings in ECA disputes

After Election Day in 2020, numerous lawsuits were taken to state and federal court, as happens after many elections. Those lawsuits addressed a wide range of allegations of voter fraud and other improprieties. The existing ECA takes some steps towards ensuring that Congress follow the decisions made by courts in those cases. For example, it says that if a state has provided a means of resolving election disputes “by judicial or other methods” that such rulings “shall be conclusive.” Still, there is wide agreement that the law is convoluted and incomplete on this point. Many have proposed a clearer provision that, if courts have decided a question about whether a state has validly determined its electors, on January 6 Congress must count those electors’ votes.

Under ECA currently, as well as with this clarification, courts do not play a substantive role in appointing electors. The Constitution clearly assigns that responsibility to the states. Instead, courts play the limited role of determining which electors the states had already appointed according to the laws in place on Election Day.

The Case For

Supporters of clarifying that Congress must honor courts’ decisions in ECA disputes observe that members of Congress raised objections on January 6, 2021, even though many of those objections had already been rejected by the courts. They also argue that courts are better suited for resolving election disputes than politicians. Proponents observe that our legal system recognizes that while Congress is well-suited to draft and enact legislation by balancing competing policy concerns, courts are better suited to resolve contested questions of law and fact that arise in a particular dispute.

Supporters further observe that courts resolve litigation about presidential elections every cycle, including the U.S. Supreme Court in 2000 in Bush v. Gore, and the dozens of decisions in 2020 that rejected President Trump’s claims of election fraud. Proponents observe that the proposal would simply ensure that in the future, Congress respects the results of those judicial decisions, as it always has in the past.

The Case Against

Opposition to clarifying that Congress must honor court rulings in ECA disputes come from opposing sides. On one side, some argue that any ECA update should go further than clarifying the existing understanding of courts’ roles under the ECA. They argue that federal courts should be given an expanded role. These opponents argue that judges in state courts are often less independent and more politically motivated, because in many states, judges are elected rather than appointed for life, like federal judges. With rising political pressures in our bitter partisan times, they argue, the independence of federal courts is needed.

Other opponents of clarifying that Congress must honor court rulings argue that the role of courts in election disputes should be even more limited than it is now, especially the role of federal courts. Many of the opponents in this camp argue that the Constitution explicitly grants the authority for determining how a state chooses its electors to state legislatures. These opponents argue that this is a wise constitutional provision because state legislatures are elected by the people and are closest to the people.

6. Limit judicial review of claims under the ECA and other federal statutes to candidates for president and vice president

There is bipartisan interest in limiting the right to file a federal lawsuit under the ECA and other statutes to candidates for president and vice president. Generally, a federal court may consider a lawsuit that raises a federal question. This clarification would prohibit a federal court from deciding a federal statutory claim if raised by someone who is not on the ballot as a candidate for president or vice-president.

This clarification would not limit the existing rights of those who could bring a claim in federal court under the U.S. Constitution, including challenges brought under the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses and Congress’s constitutional power to set the date for Election Day.

The Case For

Supporters argue an aggrieved candidate for president and vice president would certainly have a sufficient interest to pursue any serious claim under federal statutes that called into doubt the results of a presidential election. If even the candidates themselves don’t feel that there is a sufficient federal statutory question to warrant a lawsuit, proponents argue, then the country should be spared the uncertainty and disruption that could be caused by overly litigious actors wishing to create controversy where there really isn’t any.

The Case Against

Opponents argue that presidential and vice-presidential candidates aren’t the only ones who are adversely affected if those candidates were determined to have lost the election because a federal statute was violated. They argue that political parties, members of Congress, and even individuals who voted for the aggrieved candidates should be able to bring a federal lawsuit if they can show that federal court review is required to address the injury.

Presidential Transition Act

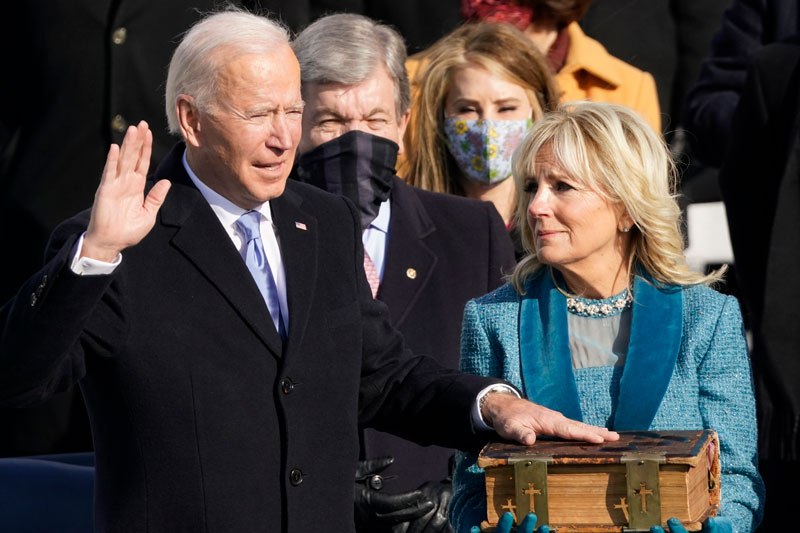

Two elections in the last twenty years have brought attention to the challenge of presidential transitions. In both 2000 and 2020, the official determination by the federal government of who the president-elect was took place several weeks after the election. As a result, the additional resources provided to an incoming administration to prepare to govern under the Presidential Transition Act (PTA) were delayed.

In 2020, because President Trump was contesting the results, the formal determination came almost three weeks after the election and two weeks after all media outlets had called the election for Joe Biden. Many noted that the delay in transition resources was especially consequential because the new Biden Administration was preparing to govern during a pandemic.

In 2000, the delay in transition resources for the incoming George W. Bush Administration was even longer. The formal determination was not made until December 14, the day that the Supreme Court effectively ended the dispute over the Florida vote in Bush v. Gore. This was a full five weeks after the election.

For most of our country’s history, the transfer of power from one presidential administration to the next was governed by a set of constitutionally grounded norms of cooperation and assistance. In 1964, motivated by a recognition that “[a]ny disruption occasioned by the transfer of the executive power could produce results detrimental to the safety and well-being of the United States and its people,” Congress formalized presidential transitions in the PTA. The act provides resources to “assure continuity in the faithful execution of the laws and in the conduct of the affairs of the Federal Government.” Those resources include increased funding, access, and in-kind support to both presidential candidates. After the election, those resources and services are significantly increased for the president-elect.

READ MORE

The executive branch structures include requiring agencies to appoint Transition Directors and prepare briefing materials, create the post of Federal Transition Coordinator, establish an Agency Transition Directors Council and a White House Transition Coordinating Council, and provide for memoranda of understanding between the General Services Administration and the transition teams.

This in-kind support begins long before the election; all (which generally means both) serious candidates receive office space, communications services, funding for printing, workshops, training for prospective appointees, and limited national security briefings. But the election itself is a significant pivot point. The president-elect receives “necessary services and facilities” that go well beyond what the campaigns had received, including funding for transition staff salaries and for travel, access to agency briefing books and personnel, fuller security briefings, and more extensive and expedited security clearances.

The enhanced support for the president-elect and the end of resources provided to the losing candidate is triggered under the PTA by the Administrator of the General Services Administration (GSA). Although the PTA directs the GSA Administrator to make the determination about the winning candidate, it provides no criteria to guide that decision.

In most presidential elections the decision has been routine and uncontroversial. With the second significant delay in 20 years and the accompanying uncertainty and controversy, a bipartisan consensus is growing for Congress to reform this provision in the PTA.

The current statute requires the GSA Administrator to “ascertain” the “apparent successful candidate.” There is significant bipartisan consensus that this provision has two major problems. The first is the problem that no criteria are provided to guide the Administrator in how to determine who the apparent successful candidate is. Second, many have noted that the GSA Administrator is not well suited for this role. The GSA oversees federal procurement and property management. The agency has nothing to do with election administration. Further, the Administrator is appointed by the current president. The GSA Administrator’s boss may be one of the two candidates (as in 2020 when the Administrator had been appointed by President Trump). In any event, the Administrator will have an extremely strong interest in the outcome of the election (as in 2000 when the Administrator had been appointed by President Clinton). In fact, the GSA Administrator appointed by President Trump noted both of these problems and urged Congress to address them in her 2020 letter making the ascertainment.

Below are three recommendations to amend the PTA to address the challenges to effective presidential transitions that were highlighted by the 2000 and 2020 elections.

Proposals

1. Create a bipartisan advisory board that reports to the GSA Administrator when it has ascertained the apparent winner

The PTA could be amended to establish a balanced, bipartisan panel of experts with experience in election law and election administration that would make its own assessment and report to the GSA Administrator when it had ascertained the apparent winner. That report would in turn trigger either (a) an obligation to for the GSA Administrator to ascertain or (b) an obligation for the GSA Administrator to explain the failure to do so. Models for such a committee are the Intelligence Advisory Board and various federal advisory committees.

The Case For

Supporters argue that a bipartisan advisory board addresses both the problem of no criteria for deciding and the problem of who decides. The experts on the committee would be familiar with the appropriate criteria for determining the likely eventual winner. As a bipartisan group, the advisory board would not have the political self-interest and won’t be subject to the same political pressures that the GSA Administrator faces as a presidential appointee.

The Case Against

Opponents argue that determining who should be on the advisory board, how much consensus is required for a decision (for example, simple majority or two-thirds), and other critical details will be challenging and overly complicated. They argue that, given the political nature of the task, the Intelligence Advisory Board is not the right example. Opponents argue that the better comparison is to the Federal Elections Commission or the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, two federal bodies that are often criticized as ineffective. Opponents also argue that the provision that allows the GSA Administrator to ignore the advisory board’s ascertainment creates a significant loophole. They observe that a rogue, politically motivated presidential appointee could still delay ascertainment.

2. Require the GSA Administrator to ascertain the apparent winner when the first of multiple specified events occur

Like the first proposal, the GSA Administrator would be required to either (a) ascertain the apparent winner immediately after the earliest of any one of several events occur or (b) explain the failure to do so. The specified criteria could include:

- Concession by the losing candidate

- State certification of a majority of electoral votes for one candidate

- No pending litigation with the potential to change the results

- One week has passed since the election

The Case For

Supporters argue that establishing this use of criteria effectively addresses both problems with the current ascertainment provisions. First, it provides the criteria that are now missing. Second, proponents argue that by making the decision less discretionary, it will reduce the political pressure the GSA Administrator could feel as a presidential appointee.

The Case Against

Like the first proposal, opponents argue that the provision that allows the GSA Administrator to fail to ascertain despite one or more of the criteria being met creates a significant loophole for a rogue, politically motivated presidential appointee to exploit.

3. Share full transition resources with both candidates if ascertainment is delayed

The PTA makes clear that during the period between Election Day and ascertainment, both candidates continue to receive support at pre-election levels. This change would simply provide that if ascertainment is delayed, for example by one week, both candidates for president would receive the full resources as if they are each the apparent successful candidate.

The Case For

Supporters argue that rather than wrestle with the difficult complications of identifying the right criteria or the right people to make such a charged political decision, it would be wiser simply to ensure that whoever is ultimately found to have won the election would not be hampered by the sort of delays that occurred in 2000 and 2020. Proponents argue that the actual expense involved in providing both candidates with the resources for a matter of days or weeks is trivial compared to the national interest in having the eventual new president prepared to govern effectively on the first day.

The Case Against

Opponents argue that this arrangement would prolong the uncertainty of not having a presumed winner. In fact, they argue it may decrease the pressure on the GSA Administrator to make an ascertainment decision. It could also discourage the apparently unsuccessful candidate from conceding. Opponents also argue that it would create added, and ultimately unnecessary, expense and effort.

State and Local Funding

All elections, including federal contests, are administered in the United States by state and local governments. A growing bipartisan consensus concludes that a steady stream of crises over the past two decades make it clear that state and local election administration is underfunded in much of the country.

Whether it was antiquated and poorly maintained election equipment that led to the recount controversy in Florida in 2000, inadequate resource planning that caused long lines in 2012, cybersecurity threats in 2016, or the crush of adapting to the reality of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, each national election seems to shine a spotlight on a different part of the system and its funding needs.

The resource challenges experienced by state and local election officials in 2020 were part of a long story, although the scale of the problems may have exceeded past experience. True, the pandemic strained everyone’s budgets. But the stress placed on election administration came on top of years of inattention. In their 2014 report, the bipartisan Presidential Commission on Election Administration wrote:

The most universal complaint of election administrators in testimony before the Commission concerned a lack of resources. Election administrators have described themselves as the least powerful lobby in state legislatures and often the last constituency to receive funds at the local level. (p. 10)

Election officials are used to “making do” with what they have. They often express pride in pulling off the complicated logistical maneuvers necessary to conduct elections on a shoestring budget.

One consequence of the frugality imposed on election administration is that services provided to voters vary considerably across the nation. Some states and localities flood their voters with voter guides, use the most up-to-date equipment, and deliver information and services on sophisticated websites. Others provide only minimal services to voters, rely on voters to figure out the details of voting on their own, and use equipment that is no longer manufactured or is incapable of being updated with the latest security patches.

Given the issues with underfunding, bipartisan interest in providing more federal dollars to support state and local governments is growing. Republicans and Democrats alike want to be able to trust our elections.

Current Cost of Elections in the U.S.

To assess whether and how much new federal funding should be provided, it is important to understand what the funding need is. Hard figures on the cost to conduct elections in the U.S., however, are hard to come by. To meet the need, CommonSense American partnered with the MIT Election Data + Science Lab to produce a new report. Much of what follows in this section of the brief is a summary of that 17-page “The Cost of Conducting Elections” report.

The MIT/CommonSense American report found that studies relying on different methodologies across the past two decades have come up with ballpark estimates that are overall consistent with one another. Those studies estimate the total cost of elections being in the range of $4 billion to $6 billion, in a “normal” year, and that spending in 2020 could have reached $10 billion.

READ MORE

Those studies include:

- The 2001 report, Voting: What Is/What Could Be, by the Caltech/MIT Voting Technology Project (VTP), estimated that local election departments spent approximately $1 billion on election administration in 2000.

- Replicating the VTP 2001 research for the President’s Commission on Election Administration in 2013, research conducted by Stephen Ansolabehere, Daron Shaw, and Charles Stewart III indicated that local election departments spend approximately $2.6 billion in election administration in 2012.

- In a 2018 paper based on the annual financial report of local governments, a research team from the University of North Carolina-Charlotte estimated that total local election costs of elections were about $2 billion, an estimate the team judged to be a “lower bound” because of how long-term liabilities and capital purchases are treated in local budgets.

- Data compiled by the California Association of Clerks and Election Officials suggest that $330 million was spent in that state to conduct both the primary and general elections in 2016, and $539 million in 2020. If these figures are converted to a per-voter basis, they are consistent with $2.3 billion being spent on both primaries and general elections in 2016 and $5.7 billion in 2020. Corresponding estimates are $2.6 billion and $3.3 billion for 2014 and 2018, respectively.

- North Dakota has published spending by local governments for statewide primary and general elections since 1980. In 2020, North Dakota counties spent a total of $3.3 million. If we extend this figure nationwide on a per-voter basis, this works out to $1.5 billion nationwide.

Because of the data problems discussed below, there is no comprehensive understanding of how much is spent on ongoing administration and how much is spent to conduct specific elections. Research by a team at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte (see Read More section above) was based on actual budgetary documents. The findings suggest that the cost of individual elections is about half of overall spending on election administration in a state, which should also account for ongoing administrative support, amortized capital expenditures, and state expenditures. Thus, the estimates in the 2010s that spending on elections was in the range of $2 billion to $3 billion is consistent with the total cost of elections being in the range of $4 billion to $6 billion, in a “normal” year, and that spending in 2020 could have reached $10 billion.

The recent report by the Election Infrastructure Initiative that aimed to estimate state and local costs to conduct elections over the next decade came up with a national figure of $53.3 billion, which is broadly consistent with these previous estimates, when converted to an annual basis (i.e., $5.3 billion).

For the sake of scale, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that local governments spent $2.0 trillion in 2018. An annual bill for $5 billion to run elections would amount to 0.25% of local government spending. The estimated cost of conducting elections on an annual basis is roughly what local governments spend managing public parking facilities.

Are current spending levels enough? A consensus exists within the election administration community that elections are underfunded nationwide, with certain locations more underfunded than others. Questions remain about how large the funding gap is, where the gaps are the largest, and how to fill them.

READ MORE

It is important to note that information about the cost of conducting elections is so elusive because states and localities differ in how election functions are accounted for in budgets. Plus, as discussed above, the amounts are such a small portion of local government budgets that it rarely occurs to officials to separately report spending on elections. Because so many employees who work in elections have other duties, accurately allocating expenses to elections can be a challenge.

The costs of conducting elections are largely borne by local governments and are often subsumed within the operating budget of a superior official, such as a city or county clerk. At the state level, expenditures are usually lumped into the budget of the chief election officer, who is most often the Secretary of State. Finally, the U.S. Census Bureau’s annual survey of state and local government finances, which is the authoritative annual study of state and local government taxing and spending, does not record spending for elections.

Background on Federal Role in Election Funding

For most of the nation’s history, state and local governments paid for the entire cost of administering elections, even in federal election years. In exchange, states were given a great deal of autonomy to determine how elections were to be conducted.

Even when Congress mandated that state and local governments follow certain procedures – such as the Voting Rights Act in 1965, the Uniformed Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) in 1986, the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment Act (MOVE Act) in 2009, and the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), commonly known as “Motor Voter” in 1994 – none of those mandates was actually funded.

Indeed, one could argue that the requirement in the Constitution that states conduct federal elections, and that Congress can make or alter the “times, places and manner” of those elections that the states conduct is the nation’s first unfunded mandate.

The federal government began to help fund the mandates it placed on states for conducting elections after the 2000 presidential election when the narrow Florida recount caused the country to turn its focus to election administration. The resulting legislation, the landmark Help America Vote Act (HAVA), was passed in 2002. Among its many provisions, HAVA required that all states utilize a statewide voter registration system, prohibited the use of punch card and lever voting equipment, and required accessible voting equipment in every polling location.

It also created the Elections Assistance Commission (EAC), an independent, bipartisan commission charged with developing guidance to meet HAVA requirements. The EAC serves as a national clearinghouse of information on election administration and oversees the development and implementation of voting system guidelines.

Unlike prior voting legislation, Congress authorized and appropriated funds to fulfill the highest-profile goals of the law. Funds appropriated in 2003 under Section 101 of HAVA ($350 million) could be used flexibly to improve election administration. Section 251 funds, amounting to $2.6 billion, could be used to meet the equipment upgrade requirements of HAVA. As of the end of 2020, the EAC reports that 94% of these funds had been spent.

After a few years of relative quiet, a presidential election once again brought renewed attention to our nation’s elections. This time it was the concern about attempts by foreign adversaries to interfere with the 2016 election through a series of cyberattacks on state and local election administrators.

As a result, Congress decided to make its first HAVA appropriations since 2010 when it appropriated a total of $880 million over three fiscal years ($380 million in FY18, $425 million in FY20, and $75 million in FY22) to be dispersed by the EAC to states and localities to improve election security, most notably cyber security. The EAC reported in September 2021 that 48% of the funds distributed to states under this program had been spent.

Most recently, Congress appropriated $400 million in the CARES Act to assist with election expenses arising because of COVID. The EAC reported in April 2022 that 95% of funds originally distributed to the states under the CARES Act have been spent.

In addition, private philanthropy contributed over $400 million to state and local election offices in 2020.

READ MORE

The largest source of these funds came from Priscilla Chan and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Several million additional dollars were contributed by Arnold Schwarzenegger to help maintain in-person polling places. Much less controversial, but still part of the philanthropic response, were in-kind donations of everything from athletic arenas and stadiums to hold socially distanced voting during the pandemic, to hand sanitizers manufactured and contributed by breweries.

The largest portion of the Chan-Zuckerberg funds was distributed by the Center for Tech and Civic Life (CTCL); a smaller proportion was distributed by the Center for Election Innovation and Research. Grants were distributed based on applications for the funds. CTCL has reported that most jurisdictions used the grants for temporary staffing, mail ballot supplies, poll worker salaries, personal protective equipment, election equipment, and cleaning polling places — all uses that were common among the CARES Act funds that were distributed by the EAC. In reaction to concerns raised about the potential abuse of such funding sources, several state legislatures have prohibited private assistance of the type provided by these grant programs.

Proposals

Congress is considering two main federal funding proposals to support state and local governments in administering elections.

1. Another one-time appropriation to address specific and pressing needs

Congress could do another round of one-time federal funding to help state and local governments address specific challenges they currently face. One leading example is to fund election security by helping states with equipment upgrades (both voting systems and voter registration systems) and other security needs.

This would be consistent with the role the federal government has played since 2002, financing the replacement of decrepit voting machines, supporting the rapid expansion of cybersecurity capacity, and helping with pandemic-related expenses.

Such an appropriation would likely be in line with some of the more recent federal appropriations in the $400 to $500 million dollar range.

2. Annual general appropriation over the next ten years

By providing a longer, ongoing, and more general funding commitment, Congress could give election administrators the ability to develop budgets based upon the reasonable assurance of the availability of such funds. This predictability is aimed at reducing the amount of hoarding that has plagued recent federal appropriations and would allow state and local governments to be more strategic with their investments. That is important because a significant portion of fundamental election administration costs are uneven. For example, the need to purchase voting equipment comes only come every ten and twenty years when that equipment reaches the end of its useful life. With guaranteed funding over ten years, state and local elections administrators would have more choice about where the funds are best invested rather than having that determined by Congress.

As with HAVA, Congress could include a financial “maintenance of effort” requirement to ensure that state and local governments don’t cut existing expenditures. These federal appropriations should be viewed as additional support, not replacement.

What is the appropriate amount of such annual support? One way to look at this is to say that ballots contain four types of elections – three types of candidates (federal, state, and local) and ballot questions (referendum, amendments, etc.). Therefore, the federal government should pick up roughly one-quarter of the cost of elections, at least in federal election years. This rule-of-thumb might amount to around $1 billion or a little more annually (roughly one-fourth of the $4 – $6 billion total annual cost).

A more ambitious approach is to base federal support on the amount of federal only voters, a sum that is proportional to the number of those people who only vote in federal elections. Because these “federal-only” voters are about one-third of all voters, this rule-of-thumb suggests an annual federal fair-share outlay approaching $2 billion (roughly one-third of the $4 – 6 billion total annual cost) for the support of elections, both current and capital expenses.

The Case For

Supporters argue that by far the most important reason to increase federal funding for elections is also the simplest: we must be able to trust that our representatives have been determined by the voice of the people. Proponents argue that leaders of both parties are eroding this bedrock of the most successful republic in history by casting doubt on our election results. Both Republican and Democratic supporters argue that given how meager current funding for administering elections is, our system is in danger of failing under the partisan stress we are increasingly placing on the system. They argue that we should invest significantly more to meet this fundamental threat to American self-government.

Supporters further argue that it is appropriate for the federal government to fund its fair share of the cost of addressing the challenge that bitter partisanship poses to trust in the nation’s elections. Proponents make three traditional arguments for the federal role in meeting the funding need.

First, they argue that Congress should play a role in funding elections because the U.S. Constitution mandates that states hold elections for the U.S. House and Senate.

Second, because Congress has imposed mandates on the states for federal elections that impact the cost of state and local elections in the four pieces of legislation discussed above, supporters argue that it should help fund these elections.

READ MORE

The NVRA currently applies to 44 states and Washington, D.C. The Act’s state mandates include allowing mail-in voter registration, providing voter registration opportunities when eligible voters apply for a driver’s license (the origin of the nickname “Motor Voter”), limiting how early states can set cutoff dates for registering, and requiring a uniform and regular voter registration list maintenance program.

These requirements create demands for management and computer systems that many states would not have undertaken absent the NVRA. As cybersecurity issues have risen in importance, these federally mandated voter registration systems have become a major point of vulnerability that states are now responsible for defending.

HAVA required states to replace outdated mechanical lever and punch-card voting machines in federal elections. It also required states to implement a statewide voter registration list.

At the time of HAVA’s passage, nearly half of voters cast ballots on lever and punch-card machines, which in some cases had been in service for a half-century. The HAVA voting equipment mandate had the effect of requiring localities to rely on computerized tabulation equipment that had a more limited useful life than they had previously chosen.

Prior to HAVA’s registration list mandate, localities frequently maintained voter lists, often using paper systems. This requirement also mandated complicated systems of computers, software, and networks that are expensive to design, implement, and protect from cyberattacks.

The third traditional argument supporters make for federal funding is that federal elections draw more voters than state and local elections. More people vote when federal offices are on the ballot than when comparable state races are at the “top of the ticket.” Because one-third of voters are best described as “federal only” voters, many supporters argue that the federal government should provide about $2 billion per year, which is one-third of the $6 billion per year in total election costs.

READ MORE

It is unclear precisely how many voters would cast ballots in even-numbered-year elections if federal offices weren’t on the ballot, but the experience of the five states that conduct statewide elections in odd-numbered years gives us a clue.

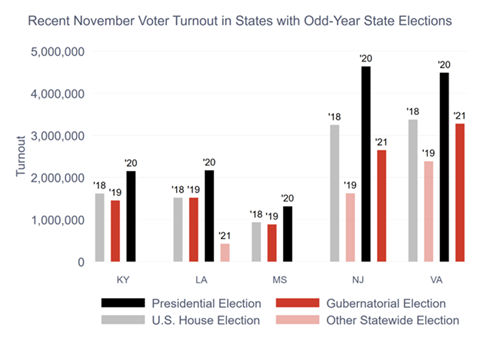

Five states conduct statewide elections for governor and state legislatures in odd-numbered Novembers: Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Virginia. The figure below shows the turnout levels for each statewide November election from 2018 to 2021, a complete election cycle. The bold black and red bars help to compare voter turnout for presidential races with that for races for governor, respectively. Looking back across the most recent presidential and gubernatorial elections in these five states, average presidential-year turnout has been 50% greater than turnout in gubernatorial years.

Comparing mid-term congressional elections (grey bars) with corresponding state legislative elections (pink bars), we see an even greater disparity between turnout for comparable federal and state elections — turnout in congressional-only elections was on average 130% greater than in state-legislature-only elections.

Federal elections attract many “federal only” voters. When it comes to the chief executives (president and governor), federal-only voters account for one-third of voters in these five states. In purely legislative elections, federal-only voters account for more than half of those who turn out.

These three long-standing arguments for a significant federal role in elections funding have been joined by a growing chorus arguing for federal funding to address the growing need to defend against the threat of cyberattacks from foreign and domestic adversaries. They argue that the national security implications of cyberattacks on our nation’s election infrastructure justify a federal funding solution.

In addition, these national security concerns have prompted a growing amount of support on the right – where the least support for federal funding has traditionally been found.

For example, in December 2021, several right leaning groups, including Americans for Tax Reform, R Street Institute, and FreedomWorks, sent Congressional leadership a letter calling for “robust and consistent assistance to state and local governments to ensure the integrity of our nation’s election infrastructure.” The letter’s signers noted that election administrators needed the assistance of the federal government “to go toe-to-toe with the offensive cyber-capabilities of foreign militaries.”

Among federal funding supporters, there remains disagreement on the terms and amount of such funding. Perhaps the most fundamental question among supporters is whether the next round of federal funding should be another one-time allocation or if there should be a move to an ongoing commitment, for example, like federal government highway funding.

Most proponents of federal funding argue for an ongoing commitment for two reasons. First, they argue it gets us beyond being merely reactive to a problem after it has already occurred. They argue that some of the past crises could have been avoided if election infrastructure were better maintained. One of these crises, in 2000, brought the country to the brink of a constitutional crisis.

Second, as experience with the 2002 HAVA appropriations has shown, when Congress provides large infusions of cash on the heels of a crisis that was caused by under-investment in election infrastructure, the reaction of state and local officials is one of two strategies, neither of which produces optimal outcomes. The first is to make hasty purchasing decisions. The second, ironically enough, is exactly the opposite: to hoard funds on a belief that things could get even worse. Both strategies reflect the cash-starved nature of election administration and the infrequency of being able to make major purchasing decisions based on a strategic vision.

The ongoing approach gains more Republican support when fewer strings are attached to the funding. Conservatives emphasize that state and local officials are in the best position to know where the money is best spent. Those on the right also argue that funding with fewer federal requirements more appropriately adheres to the constitutional mandate that states conduct elections. Some Democrats argue that establishing more specific requirements better ensures that the money is spent where it is intended to be spent.

A recent bipartisan proposal from several national organizations staked out a middle ground. Its supporters argued that additional funding should be tied to a limited set of minimum standards in critical areas such as voter registration, counting, and security. Still, virtually all supporters of additional federal elections support agree that some assistance, even if it is one-time funding, is better than no assistance.

The next most important question debated among those who support additional federal funding is how much should be provided. Last year, for example, the Election Infrastructure Initiative asked Congress to consider $20 billion over ten years ($2 billion per year). More recently, President Biden included $10 billion over ten years ($1 billion per year) in his most recent budget proposal. Others have suggested federal funding of around $5 billion over ten years ($500 million per year).

The Case Against

Opponents of additional federal funding question the need. They note that over the past five years Congress has appropriated over a billion dollars to state and local governments between HAVA Security Grants and CARES Act funding. They also point to the above-mentioned EAC report showing that states had spent only 48% ($387 million out of $880 million) of the HAVA Security Grants.

Further, some argue that the federal government has no role in funding election administration because elections should remain a state matter. After all, elections are conducted according to state laws. Certainly, the U.S. Constitution grants to states the right to determine the “time, place, and manner” of conducting elections for federal offices, with the proviso that Congress can regulate federal elections if they wish.

However, Congress has responded by placing a light hand on the levers of electoral regulation. It has set uniform federal election dates and mandated that members of the U.S. House be elected by districts. It has also enacted civil rights legislation to deter racial discrimination in voting. If states and localities comply with these congressional mandates, they should not add substantially to the cost of elections.

Therefore, if elections are underfunded, these opponents argue, this is a state problem, not a federal one. After all, the “price” for the flexibility that the Constitution and Congress largely provides to states to administer elections consistent with each state’s preferences and customs is that the states must pay for the costs of those elections. Moreover, state and local election administrators are in the best position to figure out what is needed and how to pay for it.

Election Worker Protection

Threats of violence and acts of intimidation directed toward election workers have increased significantly. Election workers include full- and part-time state and local election officials and the large temporary workforce who administer U.S. elections. The growing threat has contributed to staffing shortages and a loss of institutional knowledge because of increased election worker resignations and difficulty in recruiting new talent.

Rising concern for election workers’ security and the challenges it poses for accessible and secure elections have resulted in a growing bipartisan consensus that Congress should address the problem.

Proposals

1. Establish federal criminal penalties for threatening, intimidating, or harassing election workers

Explicit criminal penalties for threatening, intimidating, or harassing election workers would be established by expanding and clarifying existing federal statutes. For example, existing prohibitions against voter intimidation could be expanded to include intimidation of election workers. Another example would be to strengthen an existing federal statute permitting the Department of Justice to prosecute an individual who injures, intimidates, or interferes with an election official if the Attorney General certifies federal prosecution would be “in the public interest and necessary to secure substantial justice.” The clarifications would explicitly include election workers processing ballots and tabulating, canvassing, or certifying votes.

READ MORE

Research organizations from across the political spectrum have conducted studies and compiled reports on election worker threats since 2020. Key data points below are sourced from these studies and reports (see Appendix A), as well as news reports (see Appendix B):

- One-sixth of election workers surveyed have personally experienced threats

- Three-fourths of election workers report threats have increased in recent years

- One-third of election workers surveyed feel unsafe because of their election worker job

- One-fifth of election workers surveyed listed threats to life as job-related concern

- One-half of threats go unreported

- 78% of voters are concerned about the increase in threats and intimidation against election workers; 71% of voters are concerned about recruiting enough election workers due to threats and intimidation

- One-fifth of election workers report they are unlikely or somewhat unlikely to continue their work in the 2024 election

- Nearly one-third of election workers report knowing someone who has resigned in part due to threats

- Three-fifths of election workers report concerns that threats and fear for safety will hinder retention and recruitment efforts

- Election workers are overwhelmingly white, female, and between 50–64 years of age; and threats often include gender- and race-based language against women and minorities

- On February 5, 2021, chief election officers from Louisiana, Arkansas, Alabama, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, North Dakota, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington signed a resolution condemning “in the strongest possible terms, violence and threats of violence against election workers.”

The Case For

Supporters of additional federal protections for election workers argue first and foremost that ensuring election workers can conduct elections without sacrificing their safety (and that of their families) is a national imperative for our democracy to function effectively. They argue that without these measures state and local governments will be unable to retain, protect, and recruit the capable election workers our country needs to have the accurate and trustworthy elections that are essential to our system of government. Proponents observe that state election officials possess vital institutional knowledge that is difficult to replace.

Recognizing the need, ten state legislatures have weighed criminal penalties for threatening election officials since the 2020 election. Supporters argue that federal legislation would ensure uniformity and expand federal law enforcement capabilities to counteract new threats which often extend beyond the jurisdiction of a single state. They also argue that it is appropriate for the federal government to help protect state and local election workers against threats they face because they are carrying out the federal mandate to conduct elections.

The Case Against

Opponents observe that the Constitution assigns primary responsibility for conducting elections, including federal elections, to the states. Each state should make its own decisions about protecting election workers. Opponents also note that states are, in fact, acting on this threat. Another reason that opponents argue election worker security should be left to the states is that federal provisions would arguably only cover federal elections. Some also argue that state or federal laws prohibiting threats and harassment of election officials could prevent people from expressing valid concerns about how elections are administered.

2. Extend privacy protections to election workers

Threats to election workers recently have frequently taken the form of their personal information – like their home addresses – being published, or encouragement to intimidate and harass election workers and their families at their homes. To protect election workers against these threats, existing privacy protections would be explicitly extended to persons performing official duties in elections. This provision would make it unlawful to knowingly make personal information of an election official or their family public with the intent of harassment. A Minnesota bill, for example, creates civil and criminal penalties for disseminating an election worker’s personal information. Some proposed state bills would also add digital privacy protections for election officials.

READ MORE

For a more detailed analysis of existing federal laws and proposed legislation that may shield election workers from threats and harassment, see the Congressional Research Service’s December 21, 2021, report on Election Worker Safety and Privacy and Appendix C.

The Case For

Given that many threats now come in the form of disclosing election workers’ personal information, supporters argue that this specific protection is necessary to ensure that election workers can be recruited and retained so that we have secure and accurate elections.

The Case Against

Opponents make the same argument that it is better to leave these matters to the states since they are charged with conducting elections. They also observe that states are already working on expanding their privacy protections.

3. Increase federal resources for investigating and prosecuting threats to election workers and for keeping them informed about potential threats

Federal resources for gathering and communicating information about threats to election workers and for investigating and prosecuting those threats would be increased. These proposals would provide dedicated, on-going resources to respond to growing threats, initiated by federal agencies. For example, the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and the Election Assistance Commission each provide resources for protecting election worker security and responding to threats. The Department of Justice recently created an Election Threats Task Force. See Appendix D .

The Case For

Supporters argue that many of the most serious threats are efforts that cross state lines, including threats by foreign adversaries. They argue that this creates a clear need for federal law enforcement and communications to adequately protect election workers. Proponents observe that it makes little sense to establish explicit federal penalties without also providing the resources to investigate and prosecute violations. They further argue that these kinds of federal resources would complement rather than replace state efforts.

The Case Against

Opponents argue that there are already substantial federal resources being provided without legislation to create more. They further argue that since the laws protecting election workers should be state laws, so should the resources for investigating and prosecuting them.

Linking Election Measures

Before asking general concluding questions, the final policy question to consider is the linkage between the four election issues this brief has covered.

More than any other, the topic of Electoral Count Act updates is fueling the bipartisan effort to pass elections legislation in 2022. Despite the challenges the hard-fought mid-term elections create for bipartisan efforts this year, many Democrats and Republicans agree that clarifying the antiquated law is urgent and important.

Democrats are generally more interested in passing additional federal measures beyond ECA updates than Republicans. In fact, some Democrats say that they will vote against ECA legislation if Congress does not also pass additional elections legislation. Likewise, some Republicans say that they won’t vote for ECA legislation if it is tied to other federal legislative measures on elections.

The Case For

Supporters of linking elections measures argue that that nation’s critical election needs extend well beyond ECA updates. In fact, the most avid linkage supporters argue that the crucial needs extend even beyond the Presidential Transition Act, state and local elections funding, and election worker security measures discussed in this brief. Indeed, there have been serious bipartisan discussions, for example, about U.S. Postal Service reforms to support election mail and to prohibit deceptive practices such as sending out tweets or mailers falsely saying that the election is on Wednesday. Additional measures that attract Democratic support, but little Republican support, include protections against voter suppression and additional limits on actions by rogue state legislatures and governors.